A KC-135 Stratotanker aircraft with the 22nd Air Refueling Wing refuels a B-2 Spirit aircraft with the 509th Bomb Wing over Kansas Aug. 29, 2012. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Department of Defense/U.S. Air Force/Maurice A. Hodges)

It is something of a yearly ritual.

The United Nations' annual International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons falls on Sept. 26 and comes as world leaders and members of the world body convene for the annual September meeting of the U.N.'s General Assembly.

It's a nod to an important issue and one that always prompts calls for urgent action.

"The only sure way to eliminate the threat posed by nuclear weapons is to eliminate the weapons themselves," U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said in a U.N. backgrounder on the topic.

But in a world caught up in the noise of other issues — trade, political squabbles, the constant blur of social media — and with the United Nations itself conceding that its members are frustrated by the slow pace of nuclear disarmament, does the issue of nuclear disbarment have any traction?

Sr. Stacy Hanrahan, who represents the Congregation of Notre Dame at the United Nations and consistently follows and champions the issue, believes it does. But it requires a long view, she says.

At 72 and eyeing retirement from her U.N. duties later this year, Hanrahan carries with her memories of growing up during the Cold War and of the public outcry over nuclear weapons during the early years of the Reagan administration nearly four decades ago.

Sr. Stacy Hanrahan, who represents the Congregation of Notre Dame at the United Nations and is active in U.N.-based nuclear disarmament efforts (GSR file photo)

"I'm part of that cohort," she said following a Sept. 11 event at the Church Center for the United Nations Center sponsored by the Maryknoll Sisters focused on developing a culture of peace.

Hanrahan said she believes others are now taking up the issue and sees more young people attending U.N. briefings on nuclear disbarment.

"They are interested, and that impresses me," she said.

Of particular note is the connection more people make between disarmament and wider environmental issues, especially climate change, she said.

The links between nuclear weapons and climate change may not be obvious at first, she added. But if you dig deeper, it is possible to find the connections, which include the harm to the Earth of producing nuclear weapons and that the funds allocated for such weaponry could be used to protect the environment.

"I don't think we're grasping how harmful these weapons are even without using them — the money involved, resources that could be spent protecting the Earth," Hanrahan said.

One international campaign, Move the Nuclear Weapons Money, notes: "One trillion dollars is being spent to modernize the nuclear arsenals of nine countries over the next 10 years." This money, it argues, "could instead be used to help end poverty, protect the climate, build global peace and achieve the sustainable development goals."

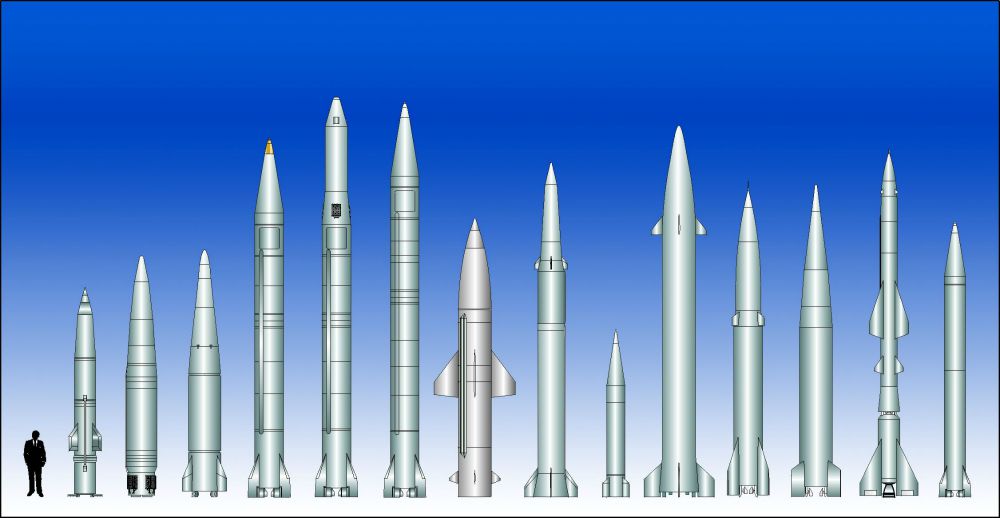

The Ploughshares Fund, a peace advocacy group, names the nine countries: United States, Russia, France, China, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, India, Israel and North Korea, noting they have a total of 13,860 weapons between them. While that number has been reduced since the height of the Cold War, it still represents a threat, the organization argues.

"When you are fleeing a forest fire it is not just direction but speed that matters," it says.

Advertisement

Sisters whose advocacy focus at the United Nations includes the environment are similarly concerned.

"There are so many dimensions to the nuclear issue," Sr. Helen Saldanha, a member of the Missionary Sisters Servants of the Holy Spirit and an executive co-director of VIVAT International, a U.N.-based advocacy group, told GSR after the Sept. 11 event.

One of those dimensions is the toll the development of weapons, the need for plutonium and other hazardous minerals, takes on the Earth itself.

"Nuclear weapons create an environmental destruction," she said.

Saldanha said there is a need for a "culture of peace" that respects the environment, and anti-nuclear advocacy's "strength is not there yet. But it could be" with increased grassroots efforts.

Judy Coode, who directs the Pax Christi International Catholic Nonviolence Initiative and who spoke at the Sept. 11 event, said the "actual use of the weapons would be catastrophic" but noted, too, that the cumulative effect of "financial and intellectual resources to develop these weapons is a sin."

A Sept. 11 event at the Church Center for the United Nations sponsored by the Maryknoll Sisters focused on developing a culture of peace. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

"What it fosters — the fear, the anxiety — has been a waste, and we need to recognize that," she said.

In its backgrounder about the Sept. 26 commemoration, the United Nations noted the international frustration over the slow pace of nuclear disarmament is partly due to increased worries "about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of the use of even a single nuclear weapon, let alone a regional or global nuclear war."

At a meeting earlier this year at the United Nations, Véronique Christory, the senior arms control adviser of the International Committee of the Red Cross, said in recent years, "debates about nuclear weapons have shifted beyond narrow 'security' interests to focus on the evidence of their foreseeable impacts. This shift in approach is to be welcomed."

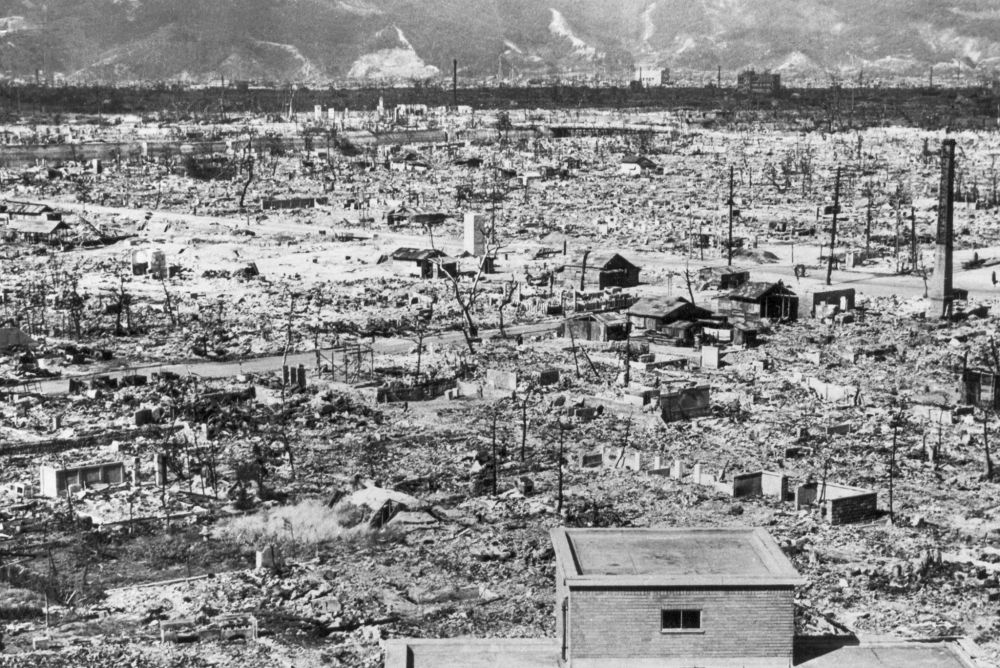

She noted that in the seven decades following the use of nuclear weapons in Japan at the end of World War II, "Japanese Red Cross hospitals have continued each year to treat many thousands of survivors who still suffer and die from cancers and other diseases directly linked to exposure to nuclear radiation in 1945."

As a result, Christory said at a May 8 gathering, "we have an even clearer understanding of the unspeakable suffering and devastation that a nuclear weapon detonation would cause. We know that even a 'limited' nuclear exchange would have catastrophic and long-lasting consequences for human health, the environment, the climate, food production and socioeconomic development."

There are other worries, as the United Nations backgrounder on the Sept. 26 event notes.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres (U.N. photo)

In addition to the nearly 14,000 nuclear weapons in the world, countries possessing such weapons "have well-funded, long-term plans to modernize their nuclear arsenals. More than half of the world's population still lives in countries that either have such weapons or are members of nuclear alliances."

There are no nuclear disarmament negotiations underway, and the "international arms-control framework that contributed to international security since the Cold War [and] acted as a brake on the use of nuclear weapons and advanced nuclear disarmament has come under increasing strain."

Though 122 countries at the U.N. in 2017 voted to outlaw nuclear weapons, the nations that have nuclear weapons and their allies did not. And last month, the withdrawal of the United States from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty "spelled its end," the U.N. said. That treaty was the vehicle through which "the United States and the Russian Federation had previously committed to eliminating an entire class of nuclear missiles."

Hanrahan acknowledges that with those kinds of setbacks, it is easy to grow frustrated.

"There aren't a lot of encouraging signs," she said. "The times are unsteady."

A recent Princeton University study confirmed these worries, concluding that more than 90 million people would perish in a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia. The project by Princeton's Program on Science and Global Security, which includes a video simulation, was "motivated by the need to highlight the potentially catastrophic consequences of current U.S. and Russian nuclear war plans," the program said. The study comes as a U.S. intelligence report concluded that an explosion last month in northern Russian coastal waters stemmed from an attempt to recover a nuclear-powered missile.

Sr. Helen Saldanha, a member of the Missionary Sisters Servants of the Holy Spirit and an executive co-director of VIVAT International, a global human rights advocacy organization that works at the United Nations (GSR file photo)

However, Hanrahan said, there is still an overall feeling that nuclear deterrence will work, that the fear of "mutual assured destruction" will prevent humans from using the weapons and nations can control the systems designed to keep a nuclear war or exchange at bay.

"Will the weapons protect us? I don't think so. It won't protect us from climate change," she said.

And efforts to modernize nuclear weapons — to make them faster, smaller — may ultimately make it easier to use them.

"Those aren't encouraging signs," Hanrahan said, adding that the use of even one weapon would lead to famine, death and severe environmental changes.

The current era of nationalism and turning away from multilateral solutions is also troubling, she said.

"Is there any good faith here?" she said. "Nationalism denies the fact that many of our challenges are international."

Hanrahan said she believes the problem will not be solved at the policy tables "unless those tables open up and those at the table changes" — for example, the participation of more women.

"We need to talk about peace and how to move it. It's a strong spiritual problem, and I think we're at a point where we can converse about the need to change the [governing] ideology — that our protection, our security, does not involve nuclear weapons."

Echoing U.N. Secretary-General Guterres, Hanrahan said the only way to prevent a nuclear war, even a "limited one," is ultimately to rid the world of nuclear weapons.

"If the desire were there, we could. But the 'denial thing' is so important," she said of the inability of humanity to deal squarely with the nuclear threat.

Christory of the International Committee of the Red Cross acknowledged the dynamic of denial remains difficult to overcome, saying, "The message often doesn't get through."

In the end, she said in an interview the week before the Sept. 26 commemoration, the best argument against the use of nuclear weapons is still the humanitarian impact they would have if used — what she called "the unspeakable suffering" they would cause. That is at the core of the ICRC's campaign against nuclear weapons.*

Hanrahan said she hopes the 75th anniversary in 2020 of the use of atomic bombs by the United States against Japan in 1945 will prompt sober reflection and renewed action.*

"It's time [for disarmament]. We have to. I believe there are people who don't want to go this way, who want to be sane," she said. Maybe, just maybe, "we'll evolve. But if we don't, we won't be here to talk about it."

*These paragraphs were updated to correct an attribution.

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]