A group of Ajo Samaritans and volunteers pause for a moment before returning to Ajo town after spending half a day dropping off water and food for migrants in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. From left are Sr. Maria Louise Edwards, Tom Zerkel, Stef Laverty, writer Peter Tran, Sr. Judy Bourg, John Orlowski, John Heid (kneeling), and Bob Hunkler. Founded in 2012, the Ajo Samaritans, who organized the day's work, respond to the death and disappearance of travelers by dropping water along migrant trails around Ajo. Their mission is to relieve suffering and prevent deaths of all persons regardless of immigration status. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Editor's note: In Part 2 of the second Frontera photo essay, Global Sisters Report presents a visual report on the high-risk border crossings into Arizona's Sonoran Desert. Lisa Elmaleh employs her 8-by-10 tripod camera and black-and-white photography to highlight the harshness of the migrant experience in the Southwest. In Part 1 on May 16, GSR focused on the nightly reception volunteers give returned migrants dropped off by U.S. Border Patrol buses at the border gate in Agua Prieta, Mexico, in early morning darkness. Read a Q&A with Sr. Judy Bourg and a Q&A with Sr. Maria Louise Edwards. And revisit the first Frontera report on Catholic sisters at the border from July 2021.

When you're a migrant fleeing a hostile homeland to cross over the U.S. border into the sprawling Sonoran Desert in the Arizona Uplands, it's mostly about the water.

It takes three or four days before you may find the first water drop-off site on a migrant trail, if you're lucky, and another three or four to get to the highway to the north. To stay hydrated in the desert, where heat exhaustion is the main cause of death, an adult should drink about 2 gallons of water a day.

Migrants can sometimes get respite from the water drop-offs along their pathways left by groups such as the Ajo Samaritans and the Tucson Samaritans.

On a day in late October 2021, a group of nine volunteers, including two Catholic sisters, a journalist and a photographer, made their way up a bare mountain, jostled side to side in four-wheel-drive vehicles, to replenish the gallon plastic jugs along the trail. Normally, they see no one, but they act as mules lugging the water to the right spots and pick up the empties and other discarded items.

"I am the trash man," said Tom Zerkel, one of the Samaritans.

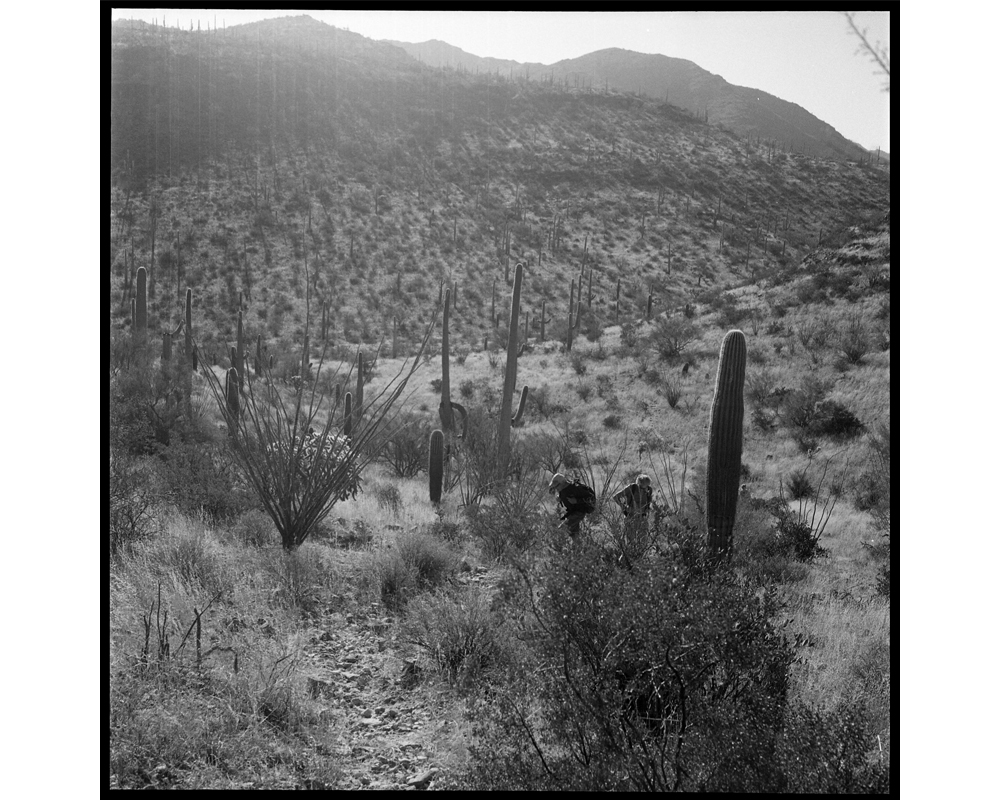

Across the ridge, about half a mile from the water-drop trail, a group of migrants in dark-colored hooded jackets walk uphill under the giant saguaros to an unknown future. Earlier, they stopped by our parked vehicles and each helped himself to a gallon jug and snacks. An Ajo Samaritan who first met them said the migrants were grateful for the water. When they spotted our larger group of Ajo and Tucson Samaritans, they hurried off but waved to us as they continued on their way.

Before heading out for an arduous hike in the desert with water and food supplies, Ajo and Tucson Samaritans huddle together to plan the drop-off activities for the day. From left are Stef Laverty, Sr. Judy Bourg and Sr. Maria Louise Edwards. The Samaritans' mission is to prevent deaths of all travelers regardless of immigration status. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Sr. Judy Bourg, a School Sister of Notre Dame and a member of the Tucson Samaritans who regularly joins the Ajo group, said that in more than 10 years of performing the water ministry she has never encountered any migrants in the desert.

Besides Bourg and Zerkel, our group included Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards, John Heid, Bob Hunkler, John Orlowski, Stef Laverty, photographer Lisa Elmaleh and writer Peter Tran.

Once at our destination, an hour drive from Ajo to about 50 miles north of the border town of Lukeville and east of Coffeepot Mountain, each of us made three trips, carrying three or four water jugs in a backpack. We left 30 gallons of water and snacks at the first location.

Then we returned to the vehicles to get more water and headed back into the heart of the desert for a 2-mile trek to our second drop-off point, passing the giant saguaros, ocotillo and cholla. The desert temperatures were in the high 70s on this trip, considered favorable weather for migrants to make the crossing, but were in the high 30s when we started that morning. In the summer, the temperatures can reach 115 degrees.

We repeated the process to a third drop-off point, taking us into the late morning.

"Humanitarian Aid Is Never a Crime" reads a banner inside the Ajo Samaritans' office. The assistance is the foundational purpose for them and other groups such as No More Deaths and People Helping People in the Border Zone.

Crossing the border illegally is categorized as "improper entry" and is a federal misdemeanor, according to U.S. immigration law. In addition, since March 20, 2020, the government has used Title 42 to deport individuals who pose "serious danger of introduction of disease into the United States." The Biden administration has announced it will suspend Title 42 starting May 23, but has met with resistance from numerous states.

Despite the dangers inherent to the desert crossing — the deterrent wall, the warnings about risks of death, and legal ramifications if they get caught — migrants continue to cross the border through the desert.

According to the Pew Research Center, 1.8 million migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border were expelled between April 2020, the first full month under Title 42, and March 2022, the latest month with available data. From October 2021 to March of this year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection expelled 118,804 migrants in Arizona alone.

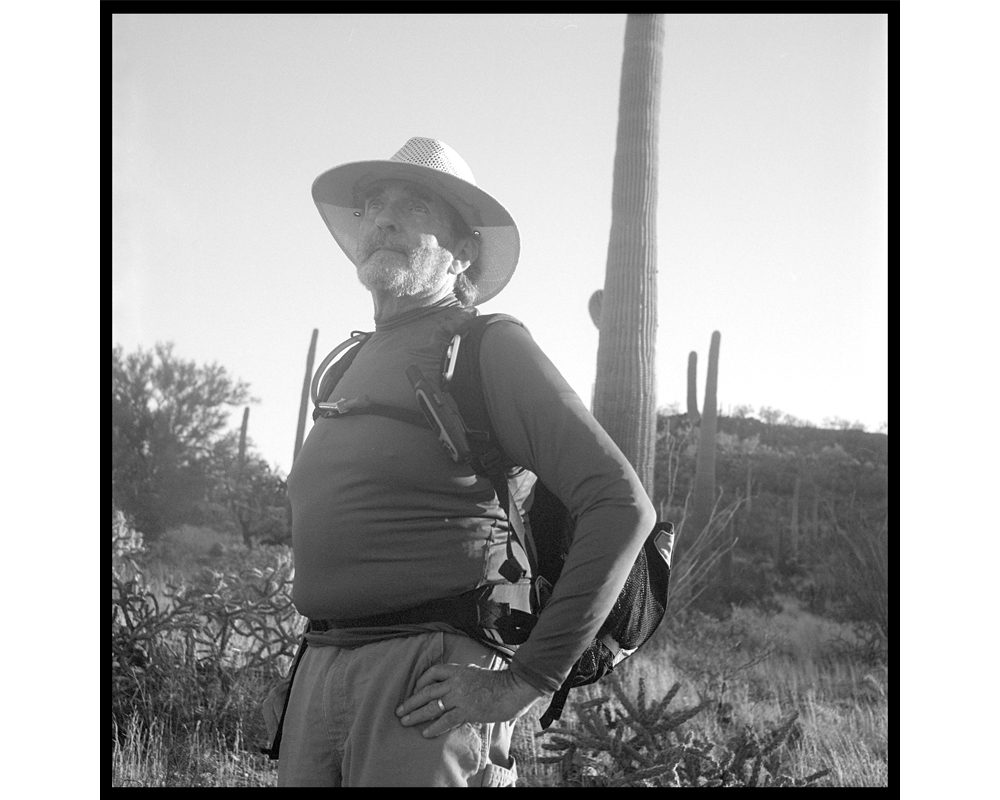

Stef Laverty, a volunteer in the water drop-off ministry along migrant pathways in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona (Lisa Elmaleh)

Dangers in the desert

Since 1998, some 7,800 migrants have lost their lives while trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border, and more than 3,500 others are reported missing, according to the Colibrí Center for Human Rights based in Tucson. The U.S. Border Patrol reports that the largest number of border deaths occurred crossing the Sonoran Desert in Arizona, the cause of death being mostly from heat exposure.

In 2021, the highest year for border crossings in three decades, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported 557 Southwest border deaths, double the annual toll of the previous two years.

A few weeks after the water drop-offs, Bourg hosted a Cross Planting ceremony at the site where a young border-crosser died from a rattlesnake bite. The sister also told of two deported women she met at a migrant center in Agua Prieta, Mexico, who heard shrill human cries at night as they journeyed through the Arizona mountains. The next morning, they said, they saw two mountain lions from afar and, when they reached the site, found human remains.

Not far from the water-drop locations and east of Coffeepot Mountain, the tribal lands of the Tohono O'odham Nation occupy 4,460 square miles with some 28,000 members living in south-central Arizona. It's the second largest reservation in the state, after the Navajo, in population and geographical size, and includes 62 miles of international border with Mexico. Long before there was a border, tribal members traveled back and forth to visit family and participate in cultural and religious events. For these reasons, tribal members opposed fortified walls on the border.

Redemptorist Fr. Ricardo Elford, who has been working in the migrant ministry for more than 50 years, said that in the 1980s thousands of migrants entered the United States through the Altar Desert in Mexico that leads into the Tohono O'odham Nation.

Wall, interrupted

After taking office in 2017, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to fulfill his promise to build the wall, consisting of 30-foot-tall steel bollards filled with concrete. Each bollard is 6 inches wide and spaced 4 inches apart, enough space to see activity on the Mexico side of the border. The foundation of the wall reaches between 6 to 10 feet underground to prevent tunneling.

The Arizona-Mexico border spans 370 miles. The Trump administration planned to build 245 miles of wall for Arizona's border with Mexico. As of Jan. 15, 2021, contractors managed to install 226 miles of the wall on the Arizona border, leaving the rest unfinished, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Not all the border has the bollard wall. Some have vehicle barriers, X-shaped crossbars or short steel posts, and fences. But these fences often sit in harsh deserts that make crossing deadly on its own.

Upon his inauguration Jan. 20, 2021, President Joe Biden terminated the national emergency and halted construction of the wall.

Advertisement

Locating the lost

The Aguilas del Desierto (Eagles of the Desert) is a nonprofit organization that rescues men, women and children who are lost in the desert while crossing the Southwestern border. The California-based organization started a yearlong campaign in fall 2021 to encourage migrants not to cross the border, said Edwards, vice president of the group.

"We will stop at every migrant shelter from Honduras to Mexico, speaking to migrants, warning them of the dangers, sharing the truth about the harsh deserts along the border," she said. Edwards has also cooperated with the Missing Migrant Program of the U.S. Border Patrol. The program provides information to would-be border crossers to convey the harsh reality of the desert.

At least for one migrant, the Sonoran Desert was his final resting place. Franciscan Br. David Buer, a member of the Tucson Samaritans, recounted an event that shook him deeply. On a long day after the last water delivery outside Ajo a few years ago, he walked up on a wash and noticed a cross. Next to the cross, a body, still fully clothed, slumped over in a seated position. Buer suspected that a traveling companion had fashioned the rustic cross after the migrant succumbed on the trail.

Buer fell on his knees, moved by what he saw. Other Samaritans walked up from behind, joined him on their knees and prayed for the deceased.

To remember those who died while crossing the desert, Buer helps organize the annual Migrant Trail walk every Memorial Day. The 75-mile walk from Sasabe, Sonora, Mexico, to Kennedy Park in Tucson takes seven days with participants from all over the country. Because of the recent resurgence of COVID-19 infections, this year's event is a one-day, virtual border encuentro (meeting) on June 4 to call for an end to migrant deaths along the border and to stand in solidarity with victims of global migration.

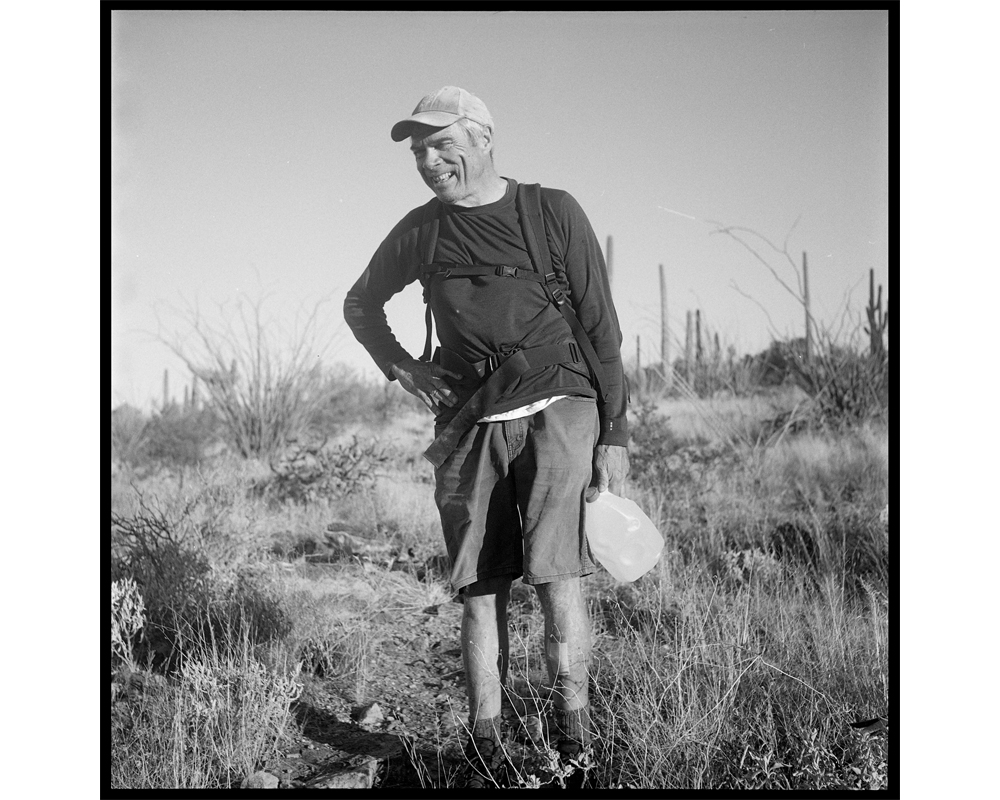

Bob Hunkler is ready for the hard day's work of walking in the desert uplands and carrying gallons of water in his backpack. Samaritan volunteers, many of whom are health care or business people, are doing mostly "grunt" work, filling up the trucks with food and water supplies, blankets and clothing items. (Lisa Elmaleh)

With a gallon jug in his hand, Tom Zerkel says to the group, "I'm the trashman." Besides doing what other volunteers do, Zerkel also scampers around the water drop-off location sweeping up empty water bottles, cans, discarded clothing items and plastic bags. (Lisa Elmaleh)

A discarded carpet shoe is used to mask footprints in the desert dust and is worn over the top of regular shoes. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Each volunteer carries as much water, blankets, food and socks as they can. Some carried 4 or 5 gallons of water, a weight of about 30-40 pounds. (Lisa Elmaleh)

The vastness of the desert can really only be felt by walking through it. From this location in the desert, the distance to the Mexican border is about 50 miles. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Two rosaries have been left in this tree by Samaritan volunteers for migrants, who know this spot on the trail north as a water drop-off site. (Lisa Elmaleh)

A volunteer takes the empty jugs back, and leaves a half-full one just in case. (Lisa Elmaleh)

John Heid, a member of the Tucson Samaritans and Humane Borders, has been working as a volunteer for years. Heid organizes the work details, checking on the supplies, the trucks and drop-off locations, taking notes on used and unused supplies, and carrying out empty bottles. (Lisa Elmaleh)

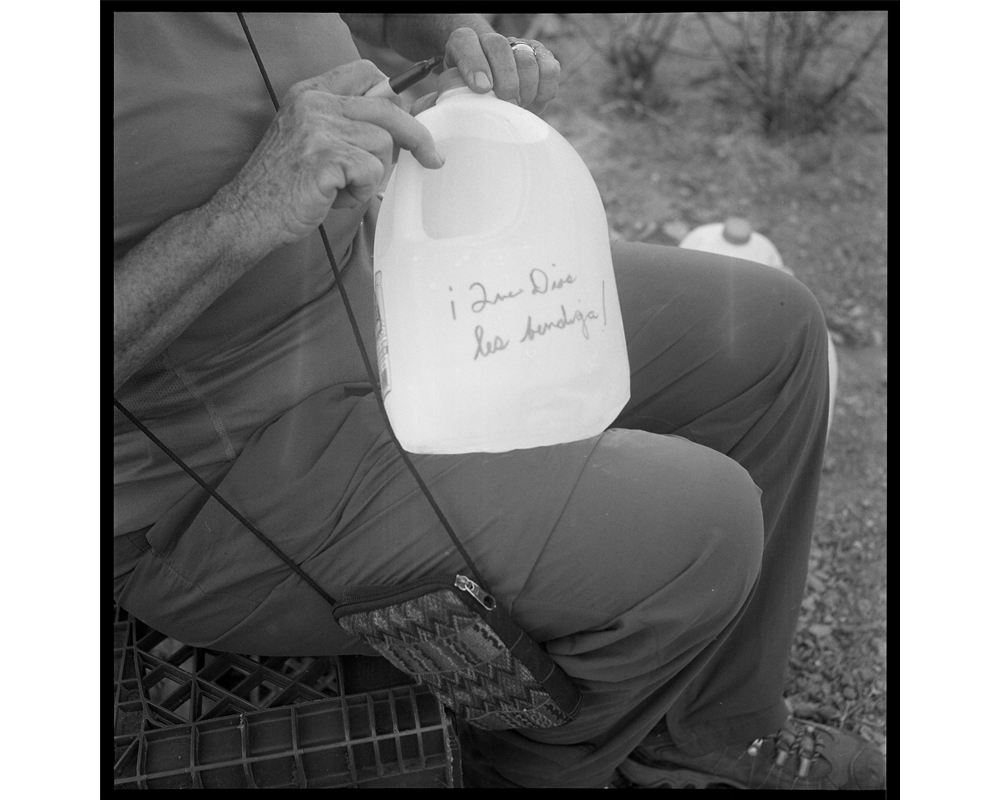

Messages are written on the water bottles left, wishing the migrants blessings and luck. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Water bottles are lined up and food is placed in buckets. Jugs are placed under milk crates to prevent animal damage to the bottles. In deciding how much to leave and where, the Samaritans base decisions on the data they record from the migrants' use of water and supplies by location and trail. "One time, we spread out in the middle of the desert and walked and looked for anything" as a clue, a volunteer said. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards is vice president of the Aguilas del Desierto, a nonprofit organization that rescues and recovers remains of men, women and children who are lost in the desert or mountains of California and Arizona while trying to cross the border into the United States. The organization also organizes a campaign to encourage migrants not to cross the desert. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Along the rolling hills and deep arroyo near the edge of the Pajarito Mountains that straddle the U.S.-Mexico border near Nogales, travelers can see a gravel road zigzagging up the disfigured faces of mountainsides, probably blasted by explosives. Where desert spoon, yucca, mesquite and cacti once stood, one can see stretches of bare soil and piles of gravel scraped by heavy construction vehicles. This road was built to transport heavy equipment and material to build the 30-foot-high steel wall along the border. (Lisa Elmaleh)

A view of the border wall looking toward Nogales, Arizona, on the left side of the wall, and Nogales, Mexico, on the right. Environmental activists and scientists say the 30-foot-high solid wall threatens animals such as jaguars and the Mexican gray wolf, and destroys natural habitats. (Lisa Elmaleh)

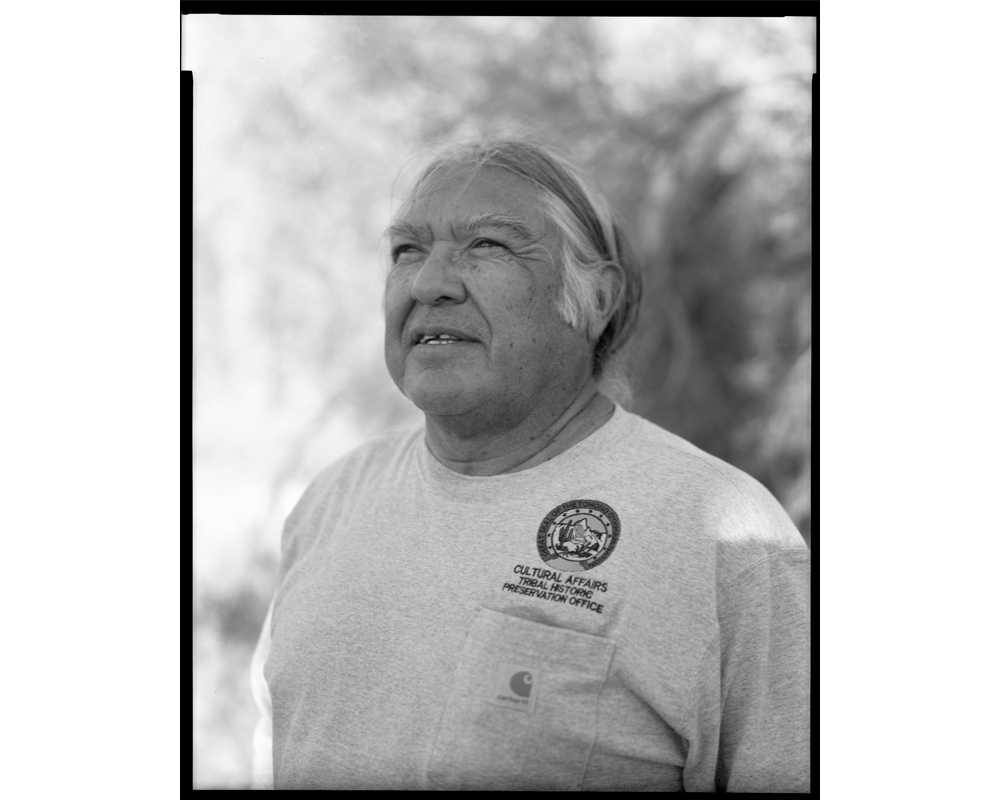

Samuel Fayuant is a cultural affairs specialist for the Tohono O'odham Nation. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Samuel Fayuant stands before Monument Hill in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a sacred place where O'odham ancestors have been buried. The wall built during the Donald Trump presidency runs through this sacred ground. (Lisa Elmaleh)

The Tohono O'odham Nation stretches from southern Arizona across the U.S. border and into Mexico. In the U.S., the Tohono O'odham land covers 2.8 million acres with some 28,000 tribal citizens. About 2,000 live in Mexico. Tribal people go back and forth across the border for domestic, religious and cultural reasons. To cross the border at three specific border crossings today, Border Patrol officers have to check their tribal identification cards. In 2006, the U.S. government and the Tohono O'odham Nation agreed to build vehicle barriers made of heavy steel (as shown here) across the nation's 62-mile border. The barriers include gates. (Lisa Elmaleh)