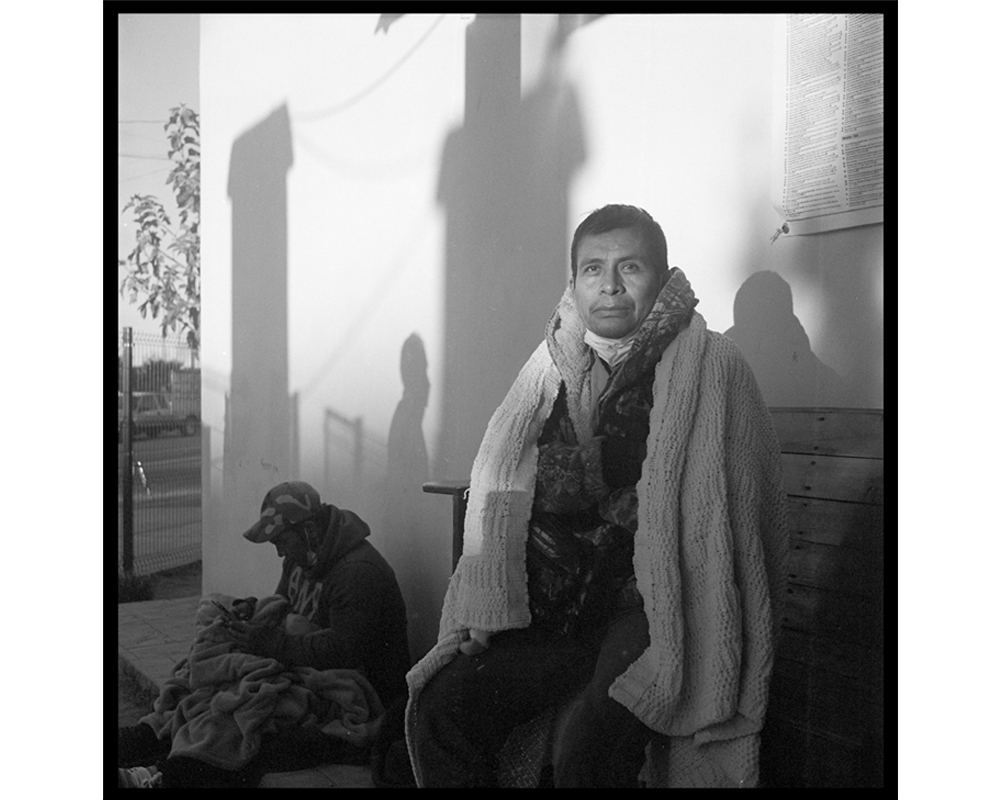

From left, Brian, Alejandro, and Humberto were among the men expelled in the middle of the night in late October at the U.S.-Douglas, Texas, border crossing. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Editor's note: In Part 1 of the second Frontera photo essay, Global Sisters Report presents a visual report on the nightly reception volunteers give returned migrants dropped off by U.S. Border Patrol buses at the border gate in Agua Prieta, Mexico, in early morning darkness. Lisa Elmaleh employs her 8-by-10 tripod camera and black-and-white photography to highlight the harshness of the migrant experience in the Southwest. Part 2, which will be published May 19, will explore the high-risk border crossings into Arizona's Sonoran Desert. Read a Q&A with Sr. Judy Bourg, and a Q&A with Sr. Maria Louise Edwards will be published May 19. And revisit the first Frontera report on Catholic sisters at the border from July 2021.

At 1 a.m. on a late October day, Sr. Judy Bourg's alarm goes off in the School Sisters of Notre Dame house in Douglas, Arizona. She marshals her three guests, who want to know about her ministry, to get ready for the 10-minute drive through the U.S. border checkpoint and on to Agua Prieta, Mexico.

They arrive at the Centro de Recursos para Migrantes, or Migrant Resource Center, a two-story building just outside the gate of the border wall there, and set to work to ready sandwiches, hot coffee and warm clothes. Bourg, a School Sister of Notre Dame, has volunteered at the center for more than a decade. She shows her guest volunteers — Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards, vice president of the Aguilas del Desierto (Eagles of the Desert), photographer Lisa Elmaleh and writer Peter Tran — the ropes.

Why do she and others perform this daily ritual in the dark of night? Because the center needs to be ready for the fresh group of deportees who will arrive in the acute hours of the day, classified as "returned or expelled." In the middle of the night, the U.S. Border officials picked them up from holding centers, put them on a bus, transported them, and subsequently left them off at the border gate outside Agua Prieta. All had been refused asylum and sent back. Back to the hunger, poverty, threats and violence they fled.

Betto Ramos, coordinator of the migrant center, says that, with the collaboration and funding assistance from Frontera de Cristo, a Presbyterian binational border ministry, and the School Sisters of Notre Dame, the center is able to help 18,000-20,000 deported migrants each year.

Somewhere nearby dogs start to howl as Bourg walks out to the border gate at 2:30 a.m. as a U.S. Border Patrol bus drops off some 30 returnees on the U.S. side. They step over into Mexico and Bourg moves in to welcome them.

She invites them to the center for food and a warm place to rest. The migrants, all men in their 20s and 30s, shiver in the declining temperatures. A volunteer doles out socks, a blanket or clothing to the men, who wait patiently in line for coffee and food. Later in the day, other groups of expelled migrants, some of whom are women, arrive. The center receives 100-200 expelled migrants each day.

Exhausted from their ordeal, they go to the second floor to crash on cots, look for space in the 300-square-foot main room downstairs or huddle outside to stay warm.

Bourg says she is deeply moved as she greets the migrants at the gate and offers comfort. "It is dark and cold, and they have no idea where they are. To be able to look them in the eyes and tell them that they are welcome into a safe place where they can rest, fills my heart," she says.

Several hours later, as the sun rises above the houses surrounding the center, the migrants shed their blankets. Two Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist walk in, smiling. Sr. Maribel Lara Hernandez cleans and can offer first aid. Sr. Emma Rias Flores heads to the kitchen.

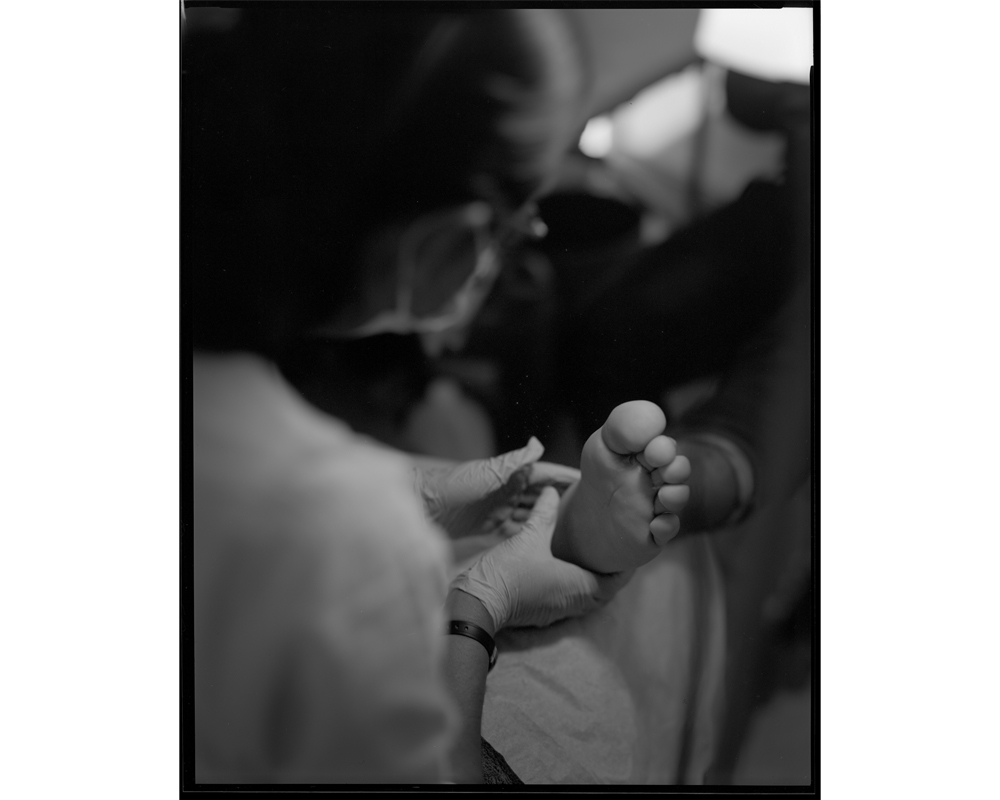

Hernandez places two chairs near a medicine cabinet to set up a makeshift clinic. One man hobbles over to take a seat, presenting his wounded foot to Hernandez. She washes the blisters, applies medication and wraps it with a gauze pad. Another migrant takes his turn, and then another.

Meanwhile, Flores stirs ditalini pasta in a large pot as a volunteer dices onion, carrot, tomatoes and red pepper. Half an hour later, Flores brings out the soup and starts serving the migrants. As the soup's aroma fills the air, the tension dissipates. Flores engages the visitors in small talk, asking about their plans and encouraging them to line up to eat. As she ladles soup, she asks where they are from and makes mental notes about what they need next — transportation to return home, medical treatment or something else. Later she follows up on their requests.

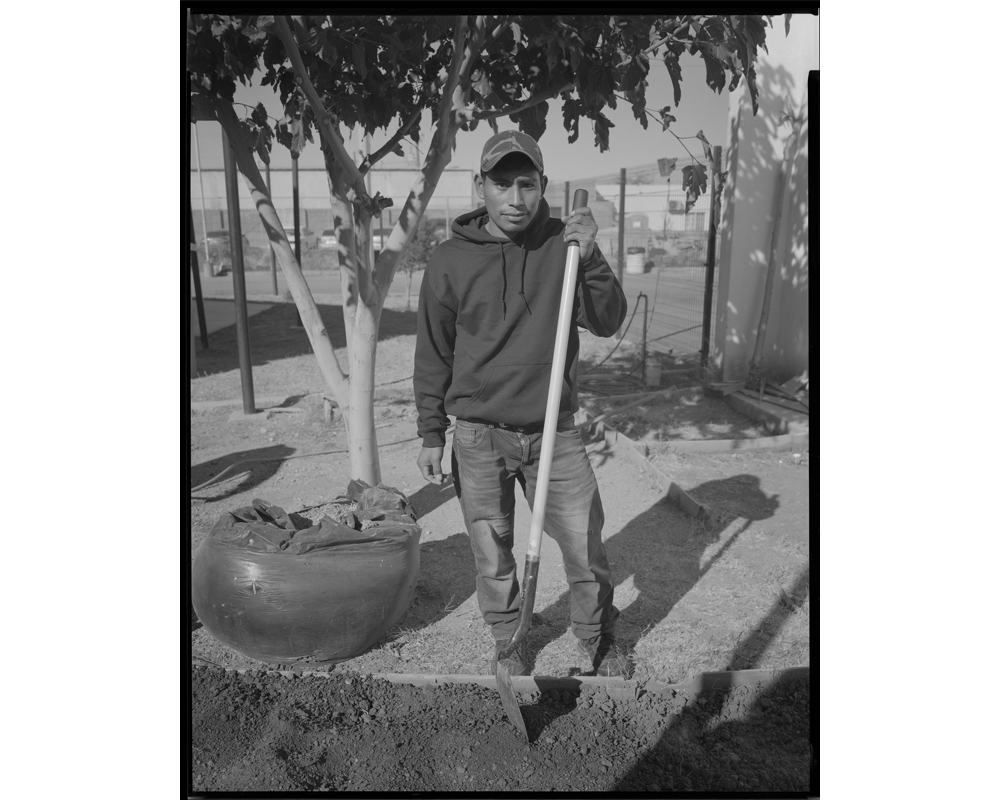

As the day progresses, the center becomes busy with activities. Volunteers work in the vegetable garden on the center's grounds. Some deportees rush to help till the soil. As the migrant center is a short-term shelter, expelled migrants will leave it soon. A small number will return to their home country, while others will attempt to cross the border again.

One migrant says that, instead of making $5 a day in his home country, he could make much more in an hour in the United States to cover food, medicine and school for his family. The financial gain from such jobs as dishwashing, cleaning, landscaping and farming continue to be a pull for migrants.

Under the Trump and Biden administrations, more than 1.7 million expulsions have been carried out since the pandemic began, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

For the last two years, the government has turned away migrants at the border, including asylum seekers, by using Title 42, a little-known emergency health law. It was launched by the Trump administration in March 2020 at the start of the pandemic in the U.S. and carried into the Biden era. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently announced that it plans to end Title 42 on May 23 because COVID-19 cases had lessened and vaccines are widely available. But that date is now in question because of Republican-led legal challenges angling to keep the policy in place.

The Migration Protection Protocols, known as the "Remain in Mexico" program, were suspended in January 2019, but were reinstated in December 2021 by order of a federal judge in Texas. They remain in effect despite human rights activists' warnings about the high risk of violence to those forced to wait in dangerous border areas.

A memorial cross was set up within the migrant center grounds to remember Andrés Facundo Marcíal, a migrant who died of thirst in the desert on June 22, 2021, at age 24. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Humanitarian help in Nogales, Mexico

About 120 miles west of Agua Prieta, Yamali and her baby daughter were waiting outside Providence Sr. Tracey Horan's office at the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Mexico. Yamali and about 35 families were deported the day before to Nogales. They came to Kino to receive food and assistance.

"I have no documents, nothing," Yamali said, tears in her eyes while her daughter was playing next to her.

Horan, a Sister of Providence of St. Mary-of-the-Woods, was taking a case history of each expelled family that came in that morning. She coordinates educational and advocacy programs that include Catholic social teaching. She collects Yamali's information and refers her to information for her next steps.

Yamali's goal was to get to Houston where siblings live. She was apprehended by the Border Patrol in Texas, expelled and dropped here in Nogales. Not knowing her future options, she said she could not return to where she came from in southern Honduras near Nicaragua.

Franciscan Sister of Christian Charity Marlita Henseler, was greeting the migrants as they entered the facility. After 12 years in parish work in Wisconsin, she wanted to use her Spanish language skill for her next ministry. She got her chance when the Kino Border Initiative accepted her as a volunteer, and her main task is to teach English to the women and children.

The Kino Border Initiative is a binational migration ministry that includes the Mexican Province of the Jesuits, several Jesuit organizations, the Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist, and the Nogales, Mexico and Tucson dioceses.

Advertisement

Short-term help away from the border

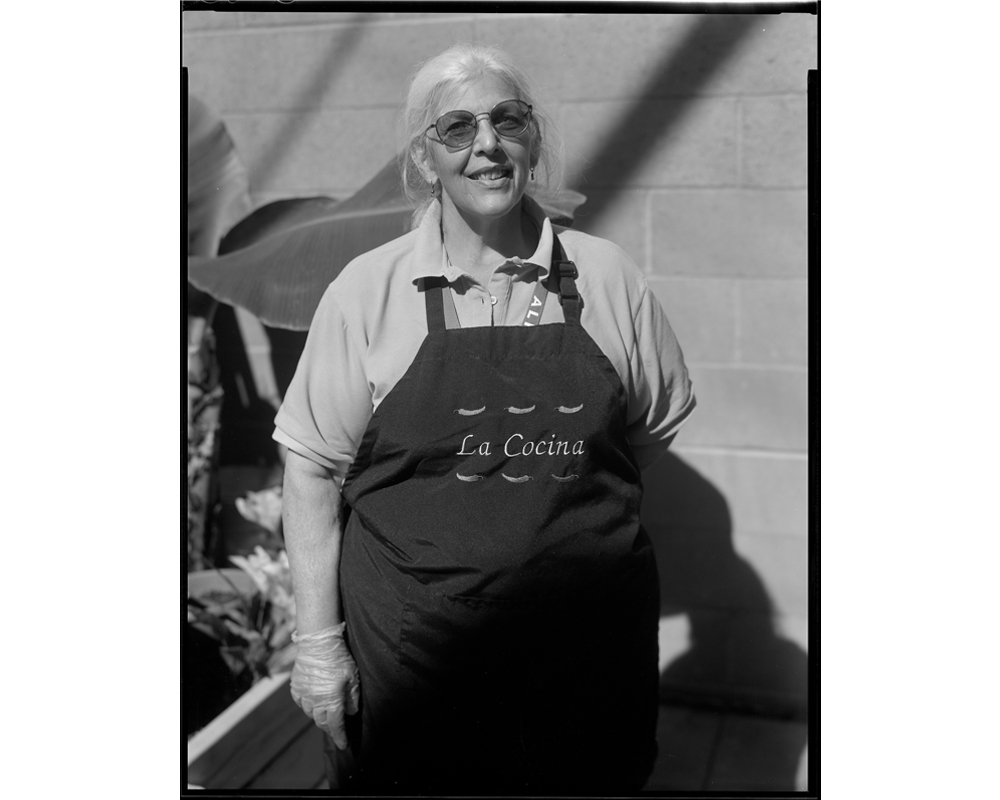

The Tucson Diocese's Catholic Community Services runs the Casa Alitas Program — Aid for Migrant Families. "We are here simply for the corporal work of mercy," Diego Lopez, program coordinator, says.

The center provides shelter, food, medicine, clothing and security. "This is the main reason we are here," Lopez says. This is a short-term shelter for asylum seekers from more than 20 nations, such as Cameroon, Congo and Haiti, who have the proper documents. Their next step is their immigration hearing in court. After the Border Patrol releases them at the center for a short-term stay, "we help them contact their sponsors, their family members, or churches that sponsor them."

Casa Alitas — "alitas" means wings — has volunteers with a variety of backgrounds, including women religious. On this October day, Maryknoll Sisters Janet Hockman, Rolande Pendeza Kahindo and Genie Natividad were helping with COVID testing of about 50 men who were just dropped off. While Hockman served soup to the men waiting in line, Kahindo was sorting food and clothing in the center's back room. Natividad, who was elected in September as vice president of her congregation's leadership team for the next six years, said she enjoyed the migrant ministry in Tucson, serving these men who were incarcerated and now are free to begin their new lives.

Other sisters who come to the Casa Alistas to work include Sisters of St. Joseph of Corondelet and Medical Mission Sisters.

Two expelled migrants wait for the sun to come up at the Centro de Recursos para Migrantes (Migrant Resource Center) in Agua Prieta, Mexico. They were among the men expelled in the middle of the night in late October at the U.S.-Douglas, Texas, border crossing. They walked across the border to the migrant center, where they could receive food and coffee, and rest for a few hours before heading out. A majority of expelled migrants will attempt to cross the border again. A very small number will return to their home countries. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Many expelled migrants hobble into the migrant center with blisters on their feet, accumulated after days of walking through the desert. Missionary Sister of the Eucharist Maribel Lara Hernandez, who serves as a first-aid nurse at the center, typically washes the migrant's foot, cleans the wounds, applies medication and wraps the injured foot with a gauze pad. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Another Missionary Sister of the Eucharist, Emma Rias Flores, works at the migrant center as a cook and social worker. She cooks, feeds the migrants and later helps direct them to local assistance as they head toward an unknown future. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Jesus, another migrant who was expelled the previous night, helps install the garden at the Centro de Recursos. (Lisa Elmaleh)

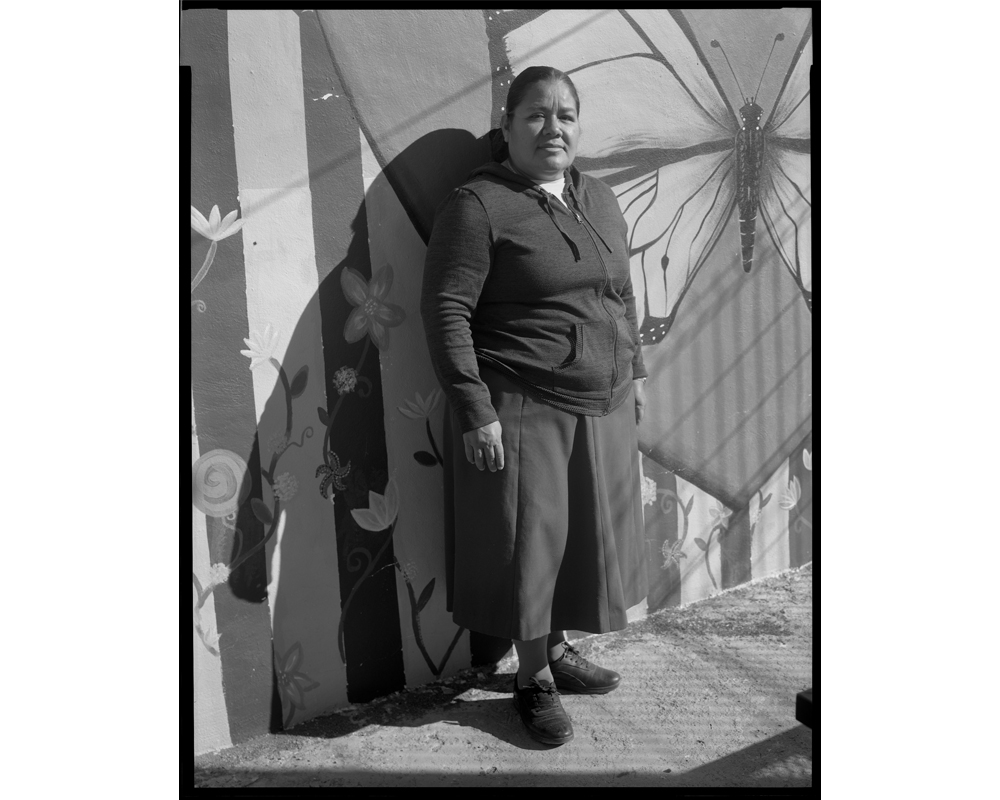

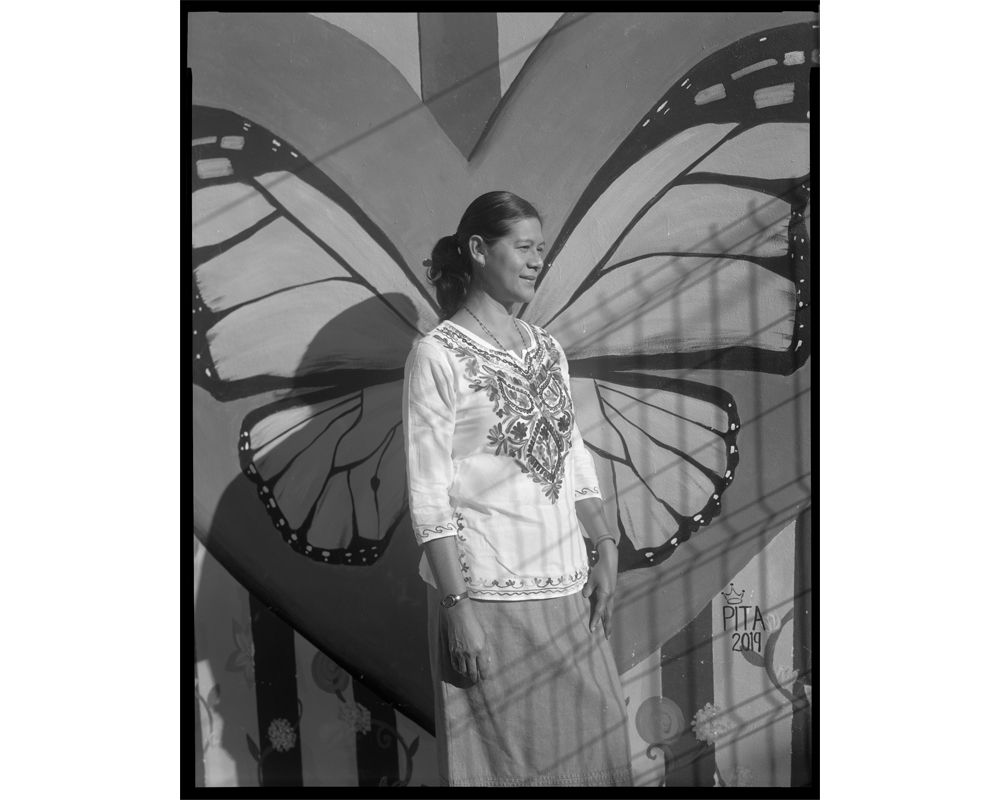

Missionary Sister of the Eucharist Maribel Lara Hernandez stands in front of the mural on the wall inside the migrant center depicting a monarch butterfly, a common symbol in Mexican culture as well as a tiny but fierce creature that migrates annually. (Lisa Elmaleh)

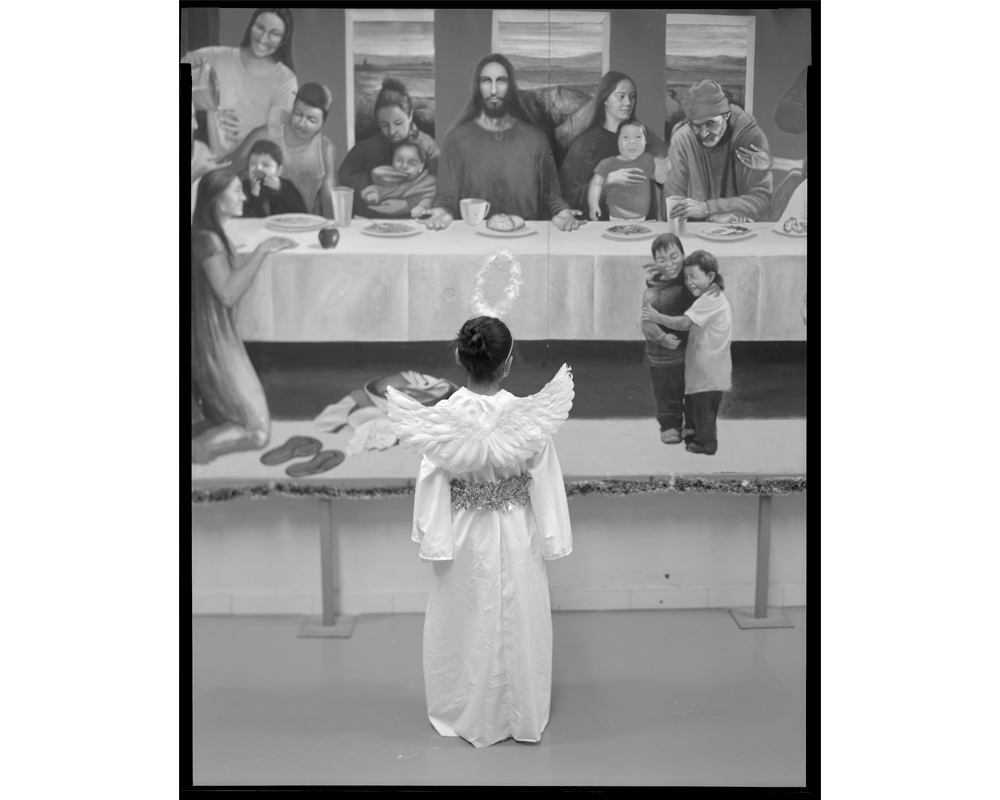

A child is dressed as an angel for Las Posadas (The Inns), a religious festival celebrated in Mexico and various Latin America countries. Families dress as Joseph and Mary to reenact the Holy Family's journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem in search of a safe place to give birth to Jesus. The child dressed as an angel stands in front of the Last Supper mural at the Kino Border Initiative, less than half a mile from the Mariposa border crossing. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Missionary Sister of the Eucharist Maria Engracia Robles, one of the Kino Border Initiative founders, is responsible for educating the migrants and would-be asylum seekers about their rights. She is also responsible for public education on migrant issues by using social media, such as Facebook, and radio. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Volunteers and migrants peel garlic for the kitchen at the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Mexico. (Lisa Elmaleh)

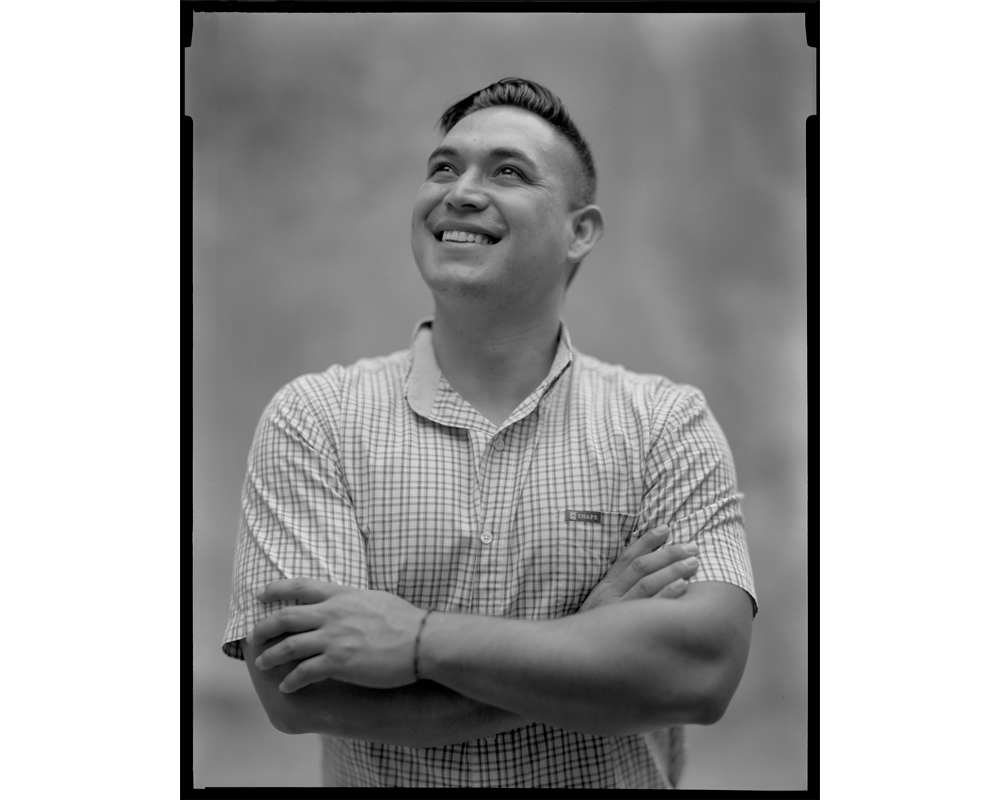

Victor Yanez Valle, a Jesuit scholastic, is director of migrant services at the migrant center. He helps expelled families get social service assistance. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Missionary Sister of the Eucharist Luz Elena Guzman Vargas oversees the kitchen, cleaning and shelter operation in the migrant center. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Franciscan Sr. Marlita Henseler from Wisconsin is a long-term volunteer at the Kino Border Initiative. She serves as a hospitality person, welcoming and directing migrants to the right place for assistance. Fluent in Spanish, her main task is teaching English to the migrants. (Lisa Elmaleh)

A woman on the Mexican side and a man on the American side meet at the fence to talk during the Las Posadas observation in December 2021. In addition to the religious gathering, migrants walked along the border wall singing songs in protest of Title 42 and the Migration Protection Protocols. (Lisa Elmaleh)

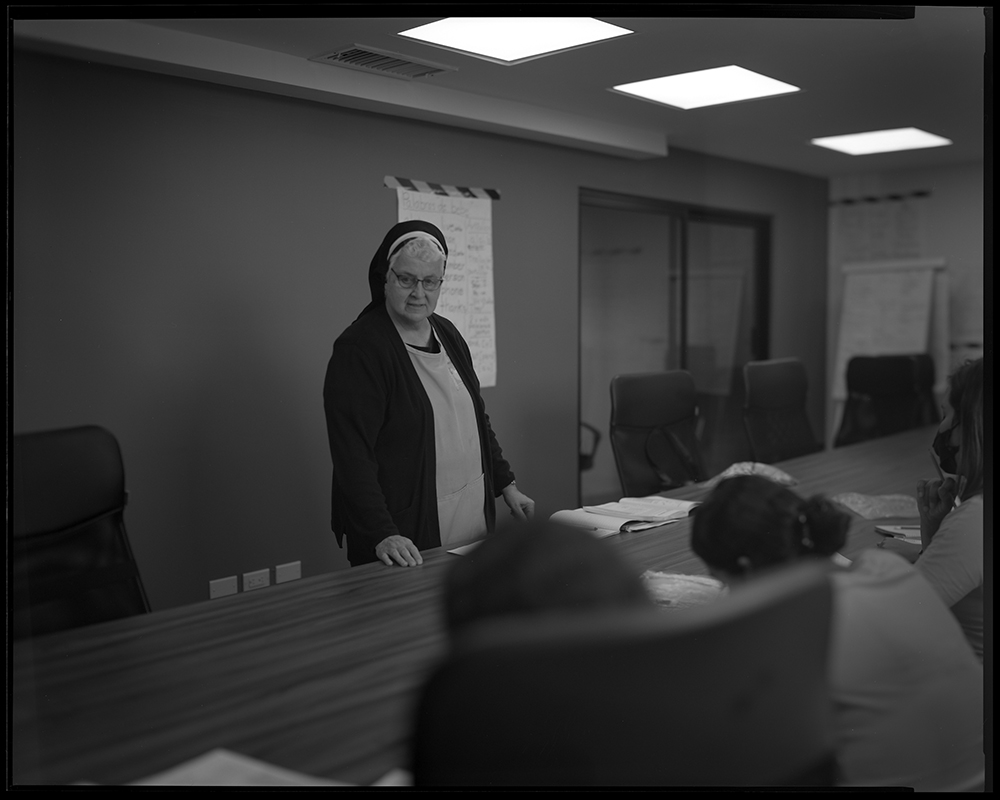

Tracey Horan, a Sister of Providence of Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, is the coordinator of education and advocacy programs at the Kino Border Initiative. She obtains intake information from each family who comes to the center for services. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Sr. Genie Natividad, from the Philippines, was one of three Maryknoll volunteers at Casa Alitas, a short-term Tucson shelter for asylum seekers from more than 20 nations, in summer and fall 2021. She has been elected as vice president of the Maryknoll Leadership Team. (Lisa Elmaleh)

Maryknoll Sister Janet Hockman volunteered at Casa Alitas in Tucson in summer and fall 2021. She has served as a missioner in the Marshall Islands and in Nepal. She now volunteers at Annunciation House in El Paso, Texas, a center that aids migrants, refugees and the economically vulnerable. (Lisa Elmaleh)

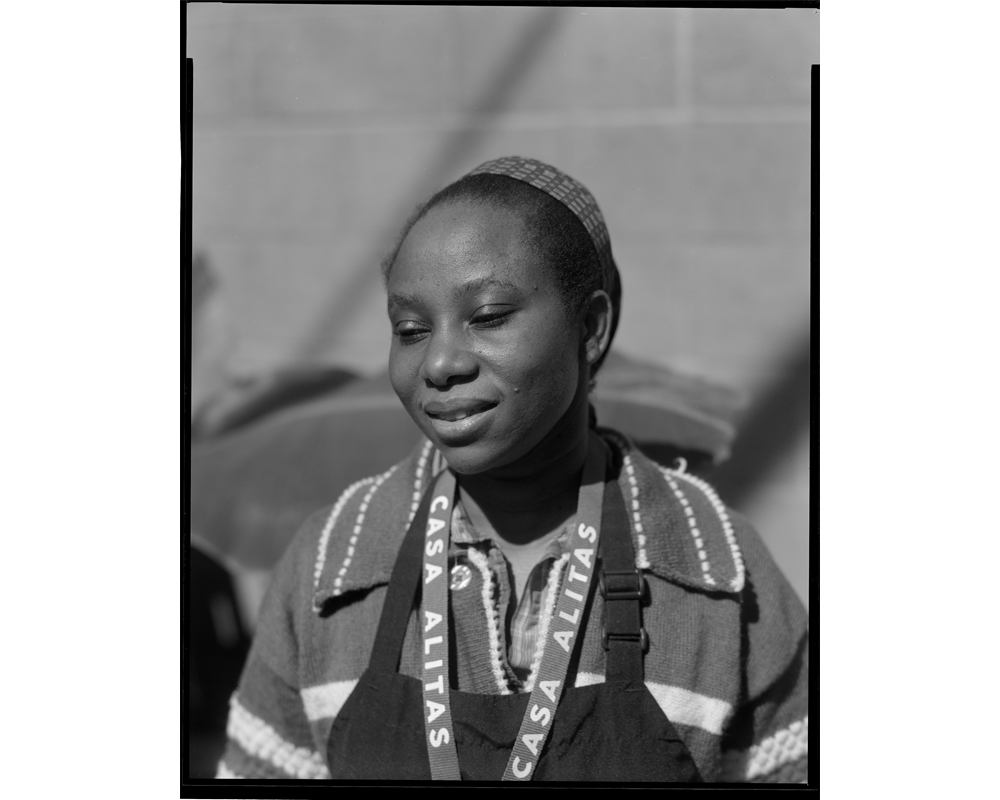

A third Maryknoll sister who volunteered at Casa Alitas in 2021 is Sr. Rolande Pendeza Kahindo. She is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. She received her first vows as a Maryknoll sister in 2019 and was assigned to East Timor. She volunteered at Casa Alitas for a time. (Lisa Elmaleh)