Benedictine Sr. Mariana Olivo Espinoza does pastoral work with families of disappeared people in Torreón, Coahuila, one of the most violent and unsafe cities in Mexico. (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

The disappearances of relatives are a painful phenomenon for a number of Mexican families. The case in Ayotzinapa, in which 43 normalistas (education majors) went missing in September 2014, may be the most well-known outside of Mexico. To date, the authorities have not been able to figure out what happened.

However, this is only one example of the reality in Mexico. According to data published by the National Registry of Missing and Unaccounted for Persons of the Ministry of the Interior, 111,929 people in the country have been labeled missing and unaccounted-for between March 15, 1964, and Feb. 27, 2023.

Although the data covers almost six decades, approximately 84% of the disappearances have occurred since the beginning of the so-called "war on drugs" that the Mexican government implemented in 2006 and continues to this day.

In addition to shootings and violence in the cities, this conflict leads to recruitment by drug cartels, kidnappings and murders that are rarely reported to the authorities and therefore do not show up in the statistics.

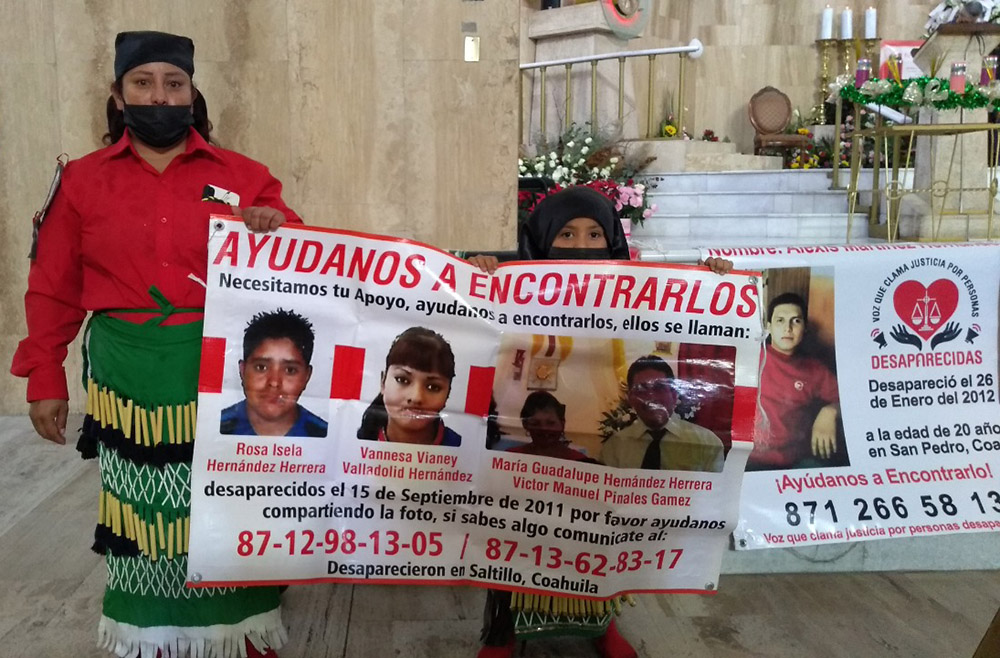

A memorial to people who have disappeared is displayed at the VIDA Group's Mother's Day memorial in 2022. (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

Benedictine Sr. Mariana Olivo Espinoza does a lot of her pastoral work with families going through these problems in Torreón, Coahuila, which is one of the most violent and unsafe cities in the country.

Olivo was a lawyer in the civil courts until she decided to join the Monasterio Benedictino Pan de Vida (Bread of Life Benedictine Monastery) 24 years ago. She did so convinced that God was calling her to put her knowledge and talents at the service of his people.

She is a sociology professor at Universidad Iberoamericana Torreón and works with the diocesan tribunal. She also ministers with groups that support human rights, families of crime and femicide victims, and an ecumenical LGBT group.

GSR: Why did you start attending to the families of those who have disappeared?

Olivo: For as long as I can remember, I have been linked to human rights groups, as my mom has always been an activist in favor of women's rights.

However, this pastoral need arose in 2007, when drug cartel violence broke out throughout the country. I was already in the monastery, and there were days when we heard gunshots when we prayed. The situation was critical. With increasing frequency, we saw our people suffering. We knew of murders, and we heard of the forced disappearance of young people.

FUNDEC Collective at the justice collectives' December 2022 diocesan pilgrimage to the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Torreón (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

Faced with all that pain, we began to preside at funerals, including those that had no one to celebrate them.

Little by little, God asked us to go further. One day, a neighbor of the monastery said to me, "Sister, will you come with me to identify the body of my son?" At that moment, I understood that this was my task in the midst of the pain of the hundreds or thousands of families who have lost their sons and daughters to violence. Families whose children were violently taken away from them and who, no matter how hard they look for them, have no trace of them.

From that day on, I asked myself: "What am I doing as a church in the face of this situation?" With the support of my Benedictine community, I responded to God's call.

What does your work accompanying victims' families consist of?

My work has been changing; however, the pain of the families is constant. For example, before 2011, I went out with the families to look for the remains of their sons and daughters in the camps that we had to call "extermination camps," such as Patrocinio, an area the size of a soccer field where collectives have found hundreds of human remains and fragments, some impossible to identify.

Benedictine Sr. Mariana Olivo Espinoza, in the blue scarf, and others search for human remains in Mexico in 2018. (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

At other times, I have accompanied mothers to the medical examiner's office to identify the bodies of their children. I have tried to be supportive and companionable. I have tried to be a sister and with this ministry, I have accompanied their pain as best I could.

I also participate in the demonstrations and protests, in the funerals, in their own celebrations and memorials. I do what I can so that together, we can discover the presence of God in the midst of so much pain and injustice.

Ever since I started this, but more so now, I focus on listening, no matter how many hours I have to put in and how many tears I have to wipe away.

Many of these women have a lot of pain and anger to heal, as well as frustration, and many times, they come to think that they no longer have faith or that God has abandoned them.

Some no longer feel they have the right to go on living after the disappearance of their sons or daughters. I know that my mission is to continue listening, comforting and giving love.

What is the most complicated thing about this pastoral care for the missing?

This work is a constant questioning of oneself and God. I say this because when I see so much pain, injustice and impunity, how do I tell the mothers of the disappeared that God is present? How do I tell myself?

Advertisement

The way of listening and faith is something that confronts and challenges me. However, I am convinced that God does not want this. The mothers of the disappeared also know this, for they firmly believe in the God who gives life, even where death reigns.

Are the collectives you're familiar with well-organized groups?

It is well-known that there are many victims, those who know each other and those who do not. That is why many families start to search and meet with others, and collectives start to emerge.

Thus arose, for example, the group VIDA [Víctimas por sus Derechos en Acción (Victims for their Rights in Action)], which began the searches in the towns near Torreón and whom I joined in 2015. I am also an ally of other groups, such as Fuerzas Unidas por Nuestros Desaparecidos in Coahuila and in Mexico.

Before Mass at the VIDA Group Memorial on Mother's Day in 2022 (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

Without such collectives, it would not be possible today for families to search for and claim the remains of their loved ones. They have forced the authorities to make plans, laws and agreements to search for the disappeared. Their work is fundamental.

With these groups, I also dedicate myself to encouraging commemorations and giving meaning to celebrations such as Mother's Day, Christmas, birthdays or anniversaries of the disappeared. We do so with the deepest respect and care because these are moments in which the absence of their missing children is strongly felt.

Each celebration is made from the awareness of the disappearance, seeking that the word of God through the liturgy also accompanies the pain, absence and despair. We want them to find hope in the God of life.

That is why we wanted to organize faith-based actions among collectives, such as the pilgrimage to Guadalupe and the Eucharist of the collectives seeking justice. This is where others that I also know very well come in, such as the Grupo de Madres Poderosas [Group of Powerful Mothers], mothers who have lost their daughters to femicide.

Eucharist at the VIDA Group's Mother's Day memorial in 2022 (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

I join and respect the needs, particularities and identity of each group, as each one is different, both in its approach and its way of proceeding. For example, each collective has its own memorial to make present and visible the death of their children.

The memorial of the VIDA group is a monument where many names of missing persons are written, and in its center, there is a rock brought from the extermination camp. That rock is a silent witness of what happened there. When we celebrate Mass, that rock is the altar.

Do you feel in danger?

I know what danger and fear are because I have experienced them firsthand. However, I also know that the danger to me is not imminent.

Rather, I fear for the group, as it is surely in the sights of the criminals, who know who we are and what we do. Not only them, but also the authorities. For example, on one occasion, we closed one of the avenues to protest at the prosecutor's office. We shouted: "Where are they? Where are they? Our children, where are they?"

Family members of those who have disappeared in Mexico are seen at the justice collectives' December 2022 diocesan pilgrimage to the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Torreón. (Courtesy of Mariana Olivo Espinoza)

This, of course, pleases neither the criminals nor the government. The National Guard took a photo of each of us who participated in the demonstration.

Should the church be involved in these issues?

Besides Jesus Christ, one of my references has been Monsignor [Óscar] Romero. I am convinced that the church has to be one of the main voices in favor of the people.

Today, when we are experiencing so much pain, the church must raise her voice to console and protect her daughters and sons.

After the murder of two Jesuits in Chihuahua, the church in Mexico made pronouncements on the "security strategy" of the current government; however, it is only one of the many cases of impunity that are being suffered in the country.

I, who am also a church, have a real commitment to the missing people and the truth. Therefore, I make God present by listening, accompanying and praying with the families of the disappeared of Torreón.