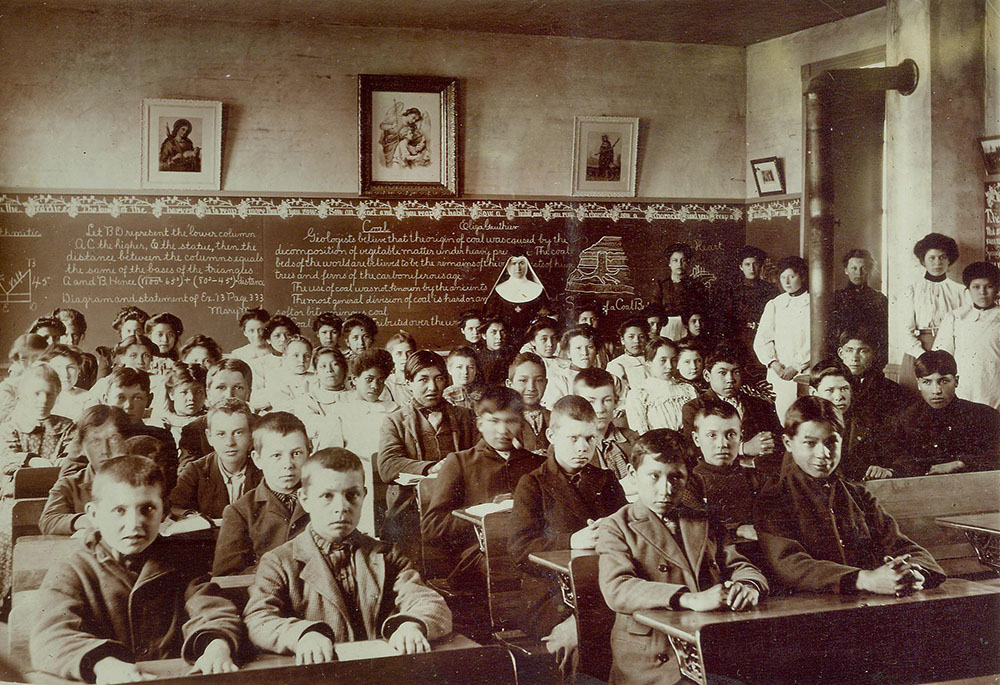

Sr. Macaria Murphy, a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, poses with students and lay staff in a classroom at St. Mary's Catholic Indian Boarding School in Odanah, Wisconsin, in this undated photo. (Courtesy of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration)

Sr. Eileen McKenzie had always been proud of her congregation's nearly nine decades of ministering to Indigenous people through their school in northern Wisconsin.

But in the summer of 2020, McKenzie, the president of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, got an email from the La Crosse County Historical Society saying its magazine was going to publish a story about the school's legacy. St. Mary's Catholic Indian Boarding School operated on a reservation in Odanah, Wisconsin, from 1883 to 1969. The historical society wanted to let McKenzie know about the article because the topic was so sensitive.

"I went, 'What? This is sensitive?' " McKenzie recalled. "I went online and Googled it, and the first article was ... about St. Mary's. I was like, 'Oh my God.' "

The 2019 story, "Death by Civilization," details the trauma the author's mother suffered from attending St. Mary's and how it affected the rest of her life. It also explains how the hundreds of boarding schools that existed for 150 years, many of them operated by congregations of Catholic women religious, were part of a federal policy attempting to destroy Native culture. Other Christian denominations, such as Methodists, Presbyterians and Quakers, ran boarding schools, as well.

"The initial learning was that there was this federal policy that we were complicit in," McKenzie said. "Then it was, 'Why didn't we know about this?' "

It was easy for the majority of Americans not to know about Native boarding schools until May 11, when the U.S. Department of the Interior released its initial report, showing they were rife with corporal punishment, including solitary confinement, withholding food, and whipping and other physical abuse. More than 500 children died at 19 of the schools, and burial sites have been found at 53 schools over the 150-year period — numbers that are expected to rise.

Children, some as young as 5 years old, were not allowed to speak their own language or practice their own religion or traditions.

Sr. Eileen McKenzie, president of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration

"People have said, 'Why did you wait so long to confront this? Why are you just waking up now to this?' " McKenzie said. "[There] was an effective erasure. In my world, that policy [of erasure] worked, but my world is a world of white supremacy. [This history] has been erased in my culture."

What happens when everything you thought you knew is suddenly wrong?

"Aren't we supposed to be the good people? Don't we educate people to bring them to a different point in life? But our intent was so different than our impact," she said. "You have sisters saying, 'Those were the best days of my ministerial life,' and other sisters saying, 'This is systemic racism.' "

McKenzie doesn't deny abuse took place at St. Mary's, but notes the only way to know what happened will be from the stories of former students. Even if there had been no abuse, she said, the school was — unwittingly or not — part of an evil policy.

Pope Francis is scheduled to visit Canada July 24-30 to apologize to Indigenous peoples for abuses at Catholic-run boarding schools there. Canadian schools were modeled after those in the United States, but have received much more attention: In 2008, after thousands of school survivors filed lawsuits, the Canadian government formally apologized, set up a $1.9 billion compensation fund and established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as 60 Minutes reported.

That process brought years of attention to the Canadian schools; they were back in the spotlight starting a year ago when 200 unmarked graves were found at a school site.

Advertisement

McKenzie's congregation and a handful of others, as well as church officials and laypeople, are part of the Catholic Native Boarding School Accountability and Healing Project, which is working to address the role the Catholic Church played in the government's attempted cultural genocide. The group, known as the AHP, grew out of a grassroots group formed in the fall of 2020 known as Catholics for Boarding School Accountability, and another that formed in April 2021; the two merged a few months later.

Maka Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux member who is the executive director of truth and healing at Red Cloud Indian School at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, is on the AHP steering committee and said truth and accountability have to come first before healing can begin.

"For Native people, this is not news; this is history. This is family history," Black Elk told Global Sisters Report. "It's really powerful when you realize there is almost no Native person in this country who does not have someone in their family who attended one of these schools."

Maka Akan Najin Black Elk is seen in front of the Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, May 5, 2021. (CNS/Courtesy of Red Cloud Indian School/Marcus Fast Wolf)

The sacrament of reconciliation, after all, begins with an acknowledgement of sin.

"It's really important that as a Catholic Church we — in all the ways we can — step forward and take ownership of this history," he said. "I think the AHP is a great first step."

Learning the truth

Sr. Sue Torgersen, of the Congregation of Sisters of St. Joseph, is also on the AHP steering committee and said it is difficult to learn the truth of these schools.

"It's a surprise for the religious communities themselves to find they had this history and that it was not all that benign," Torgersen said. "These communities didn't deliberately set out to be perpetrators, but they were."

That pain, of course, is nothing compared to the pain of the survivors, she said.

"We were operating in a system that was, in its intent, cultural genocide. So what do we do about that now?" Torgersen said. "There's a lot of accountability needed on the part of the government and the various churches involved, including the Catholic Church."

Torgersen said that subjecting generations of Native Americans to boarding schools — attendance was mandatory — has affected almost every facet of Indigenous life.

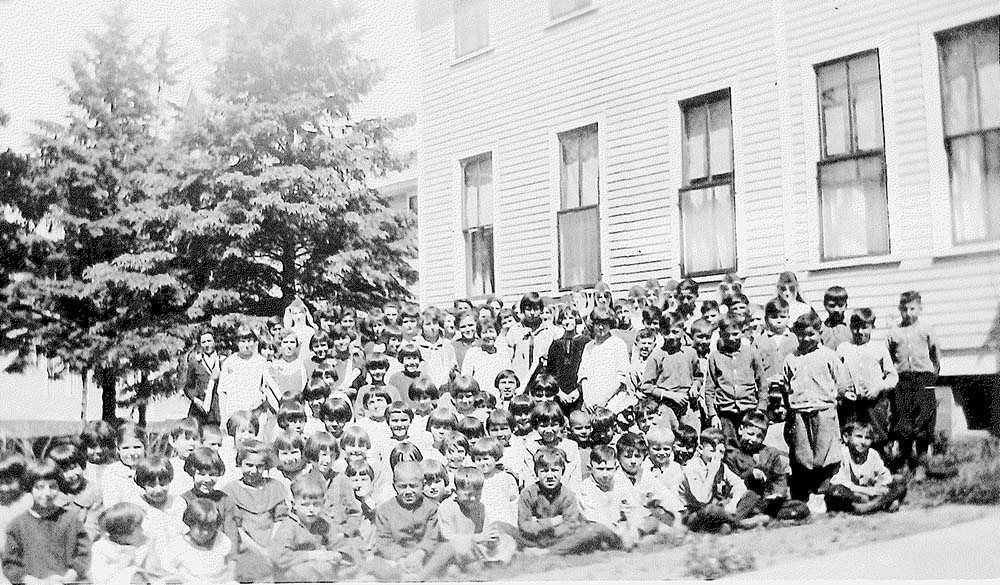

St. Mary's Catholic Indian Boarding School students pose for a photo during a school picnic during the 1922-23 school year. (Courtesy of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration)

"There was a breakdown of their culture. The not learning how to love, not learning how to parent," she said. "It's hard for us to wrap our arms around the enormity of the harm that took place. It's coming back to haunt us now, but it's haunted Native American people all along."

Torgersen said one of the first things congregations can do is examine and make available their historic documents. But that, also, is challenging: Veronica Buchanan is the archivist for the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati and the executive secretary of Archivists for Congregations of Women Religious, which is working to help congregations figure out what records they have and can share.

Buchanan said many congregations do not have records as they may have been lost or seen as unimportant and thrown out, or the records they have are so unorganized they are useless — she described one archive as "boxes in an attic that haven't been touched in 50 years." And while many congregations' archivists are now laypeople with professional archivist training, some are sisters who view their role as protecting the archives' contents from outsiders. Some may be afraid of legal liability.

She also cautions that even if there are extensive records that are made available, they might not be what people are looking for.

Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration who served the congregation's St. Mary's Catholic Indian Boarding School during the 1922-23 school year in Odanah, Wisconsin (Courtesy of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration)

"The bulk of what our community did was school work ... but the bulk of our collection is faculty reports," Buchanan said. "We really just have records that relate to the sisters that were there."

Records such as student transcripts or enrollment lists usually revert to the local diocese, she said, so those might not be in sisters' archives. Those records could also be covered under federal education privacy laws.

Finding the whole story

Libby Comeaux, a Loretto co-member who in 2021 co-wrote a Resolutions to Action article for the Leadership Conference of Women Religious on boarding schools, said congregational records are important, but are only one narrow side of the issue.

"If you're doing an internal review of your archives, you're not going to get the whole story. You're going to get the story the sisters told themselves," Comeaux said. "We do not know the whole story ... and we have more to learn than our archives can tell us."

She said the key to all of this will be relationships: Building relationships with tribal nations that were affected will allow survivors' stories to be told and preserved, guide what records need to be shared, and allow for a healing process to begin.

Schoolwork and an art exhibit at St. Louis Day School, a ministry of the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia, which operated the school until 1915.* (Courtesy of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, MU ID 11488, Raynor Memorial Libraries, Marquette University)

Comeaux said the Lorettos had already begun building a relationship with the Osage Nation when the news broke that the bodies of more than 200 children had been found at a Canadian residential school, prompting the Loretto congregation to examine its records for the three schools it operated and another it sent sisters to work at.

She said she hasn't found evidence of abuse in the documents, which is no surprise, but is working with the Osage on a possible event where tribal members will come to the motherhouse to tell their own stories. She knows those stories might be harrowing.

"We will listen to whatever they have to say," Comeaux said.

McKenzie said the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration are building a relationship with the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians, as well as other tribes whose children attended St. Mary's. But relationships take time.

"I understand the impatience, the pain and the rage. But we are just kind of waking up to this, and we still have a lot of learning to do," she said. "We're not afraid of legality or finances. ... We recognize that when you go in with your own agenda, it doesn't work. And when you're the perpetrator, it changes everything — the last thing we want to do is just say we're going to make it all better."

Retired professor, poet and artist Denise Lajimodiere, author of a collection of 16 oral histories of boarding school survivors titled Stringing Rosaries, and a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in Belcourt, North Dakota, said healing can't begin without accountability, which requires releasing school records and acknowledging the cultural genocide that took place.

"The church has to look at themselves," Lajimodiere told Global Sisters Report, but Indigenous people also have to find healing within themselves. "We have to learn to forgive the unforgiveable. How do we do that?"

Denise Lajimodiere, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in Belcourt, North Dakota (Courtesy of Denise Lajimodiere)

Pope Francis made an initial apology for the Canadian schools earlier this year. It's unknown if his in-person apology will be for those in the United States, as well, but even if it is, Lajimodiere said that isn't enough.

They do help, though. "I believe in apologies," she said. "And his appears to be a sincere apology that Canadians are accepting. But the First Nations people there had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and we need that in the States."

Last year, the Sisters of the Order of St. Benedict of St. Joseph, Minnesota, apologized to the White Earth Nation for their schools. The congregation and its colleges — the College of St. Benedict and St. John's University — are also working with the AHP.

Prioress Sr. Susan Rudolph said she is reluctant to talk about the letter of apology she wrote, because it is a minor issue in a much bigger need to make things right.

"The prime issue is helping to right a wrong, to bring to public view the fact that our government established an assimilation policy which attempted to destroy the culture of the Native American people," Rudolph said. "Our community happened to be involved in that — partly out of ignorance, but no matter what our motives were, the policy itself was wrong. All the things surrounding that ... is kind of secondary right now."

Torgersen said it is irrelevant that most of the sisters involved in boarding schools are long gone.

"Is [what happened] our fault? That doesn't matter," she said. "What matters is how we can be agents of healing."

*An earlier version of this caption misidentified the congregation in the photo.